Modern entrepreneurship began at the turn of this century with the observation that startups aren’t smaller versions of large companies – large companies at their core execute known business models, while startups search for scalable business models. Lean Methodology consists of three tools designed for entrepreneurs building new ventures:

- The Business Model Canvas – to write down all the hypotheses about a new business;

- Customer Development – a process for testing those hypotheses outside the building;

- Agile Engineering – to rapidly build minimal viable products to test product/market fit.

These tools tell you how to rapidly find product/market fit inside a market, and how to pivot when your hypotheses are incorrect. However, they don’t help you figure out where to start the search for your new business.

A new tool – the Market Opportunity Navigator – helps do just that. It provides a wide-lens perspective to find different potential market domains for your innovation, before you zoom in and design the business model or test your minimal viable products. This new framework can act as the front-end of Customer Development. It helps figure out the most promising starting position – market domain – for your customer development process. And it helps identify promising Plan B’s and new growth options if you have already embarked on your innovation journey.

Over the years, I have seen many startups and innovation projects perform a painful “re-start” to completely new market domains. With a little more thinking up front these entrepreneurs and innovators could have identified more promising business contexts to play in, and thus avoided this difficult pivot down the road. But while the academic literature is full of papers covering market selection and the literature has some popular books (Blue Ocean Strategy, et al.) there is a lack of easy-to-use tools to do so.

In large companies and government agencies the problem is even more acute. Where do we spend our limited time and resources on our next moves? While the Innovation Pipeline tells us how to go to from sourcing to delivery how do we prioritize our choices? The Market Opportunity Navigator is a useful adjunct to the curation and prioritization steps.

Just like the Business Model Canvas, the Market Opportunity Navigator has closed the gap between academic theory and books by offering a simple, visual way to navigate the process of how to select what market to start with. Developed by Prof. Marc Gruber and Dr. Sharon Tal and based on hundreds of cases they studied during their practical and academic work, the Market Opportunity Navigator is described in their new book, Where to Play.

In three simple steps the Market Opportunity Navigator can help you:

- Identify a portfolio of market opportunities stemming from your technology or unique abilities

- Reveal the most attractive domain(s) by evaluating the potential and challenges of each option

- Prioritize market opportunities smartly to set the boundaries for your lean experimentations

I asked Sharon and Marc to summarize why market selection is important and describe an example of how to use it.

Different Playgrounds mean different Rules of the Game

There are many ways in which you may have identified a market for your business. Some of you may have identified a market need based on your own experience, or you may have been approached by potential customers, or if you are corporate innovator you may have applied an innovative solution to an existing target market. Yet, are you sure that this is the best opportunity? Could there be greener pastures (larger markets, more profitable markets, etc.) out there for commercializing your technology or unique abilities?

Taking the time to reveal the most promising market – the best starting position – before you engage in a focused customer development process is critical, because market domains vary in their value creation potential, competitive landscape, regulatory regime and risks associated with launching new products. In fact, by not asking “Where to Play” innovators risk choosing an inferior playground – one that does not allow the project to prosper. Beyond the possible loss of revenues, this early decision may be difficult to change, or even irreversible: it influences how you develop your technology going forward, raise money, write patents, recruit employees and pick a brand name. If re-start in another target market is required, such a pivot is painful, costly, and sometimes even impossible.

Finding the best starting position is a learning process that takes time and bandwidth – two scarce resources. So instead of taking a deliberate step back to understand their portfolio of opportunities, entrepreneurs and innovators often just start running. They make a bet and engage in customer development experiments – adopting “local” pivots in a relatively fixed context, until a scalable business model is (hopefully) revealed. This can be a big bet! The search for product/market fit and for a scalable, promising business model should therefore begin with uncovering and understanding the different market contexts in which you can play. In fact, by adopting a wider lens, the search process shifts from 2D (finding a product-market fit) to 3D (finding multiple product-market fits in different market contexts).

Academic research published in Management Science investigated 85 VC-backed startups and offered a conclusion that seems obvious in hindsight: “look before you leap.” The big idea was that experienced entrepreneurs tend to generate a portfolio of market opportunities before deciding where to play, thereby laying the ground for significant performance benefits. In other words, understanding your arena of opportunities is a key asset for entrepreneurs and innovators.

Identifying your Arena and Choosing Where to Play

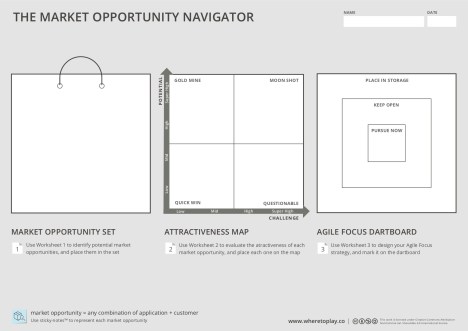

The Market Opportunity Navigator provides a visual framework to discover, compare and prioritize different market domains and business contexts. It helps you to think about your arena, rather than your industry – a key mindset shift in today’s competitive landscape.

The Navigator walks you through a three-step process that helps you to make a more informed choice. It does so in a friendly, intuitive manner, with a visual design board and 3 worksheets to guide the process.

You can download the Navigator and its worksheets here.

You can download the Navigator and its worksheets here.

Putting it all together: A Superset of Tools

Mapping out your market opportunities to understand your most promising starting position generates valuable insights for your innovation journey. In short, the big-picture view provided by the Navigator helps you zoom-out to understand “where to play,” while the detailed views of the lean approach and the Business Model and Value Proposition Canvases help you zoom-in and understand in detail “how to play.” Together, they create a superset of tools that supports you in an iterative learning process until you find a scalable, promising business.

Having a market opportunity portfolio to draw from offers an additional benefit. By having gamed out multiple markets, you can bake agility into the DNA of your venture – a key component in the Lean methodology. It allows you to carefully select and keep open backup and growth options. If a “re-start” is eventually required, it will be less painful and less costly.

Let’s take a look at an example from the startup world to see how the Market Opportunity Navigator works.

We Can Fly Anywhere – but Where Do We Go First?

Flyability develops drones to inspect difficult-to-access locations. In theory, they can custom-build their drone to perform different jobs in completely different markets: industrial inspection, search and rescue, entertainment or surveillance – to name but a few. Each of these markets varies significantly in its business context and in its promise for growth. Furthermore, each market would require its own customer development process to reveal a scalable, repeatable business model – clearly a demanding process that is difficult to run simultaneously in multiple domains.

So how did Flyability find its best starting position – the initial market domain where the founders should engage in detailed customer discovery and build their business? They used the Navigator and its three worksheets to guide their process.

Worksheet 1: Generate your market opportunity set

The founders’ first idea was to use the drone for observing critical disasters, like the reactor meltdowns in Fukushima, Japan. Yet, by going through the first step of the Navigator, the team began to uncover alternative markets where their drone could add value for customers. Among others, they considered drone-based inspection of boilers in thermal power plants, the inspection of oil & gas storage tanks, and intelligence-gathering by police forces. Overall, five market domains seemed interesting and required further evaluation.

The founders’ first idea was to use the drone for observing critical disasters, like the reactor meltdowns in Fukushima, Japan. Yet, by going through the first step of the Navigator, the team began to uncover alternative markets where their drone could add value for customers. Among others, they considered drone-based inspection of boilers in thermal power plants, the inspection of oil & gas storage tanks, and intelligence-gathering by police forces. Overall, five market domains seemed interesting and required further evaluation.

Worksheet 2: Evaluate market opportunity attractiveness

Using the second step of the Navigator, the team systematically examined the potential of each market and its unique challenges. This allowed Flyability to map out their options and visually compare their attractiveness. Gradually, it became clear that thermal power plants were a “gold mine” option worth playing in. They could now use the Business Model Canvas and the lean experimentation processes to design and validate a scalable business model within this market.

Using the second step of the Navigator, the team systematically examined the potential of each market and its unique challenges. This allowed Flyability to map out their options and visually compare their attractiveness. Gradually, it became clear that thermal power plants were a “gold mine” option worth playing in. They could now use the Business Model Canvas and the lean experimentation processes to design and validate a scalable business model within this market.

Worksheet 3: Design your agile focus strategy

Once the founders chose their primary market, they could leverage alternatives to create a more agile company by mitigating risk and avoiding locking-in. Specifically, using the third step of the Navigator, the founders designed a small portfolio of backup and growth options that they would keep open. This foresight laid the ground to early key decisions that have long-term consequences, like how they developed their drone or chose their brand name. In addition, it helped them clearly define which options they would place in storage for now (as focusing is about saying no more than anything else).

Once the founders chose their primary market, they could leverage alternatives to create a more agile company by mitigating risk and avoiding locking-in. Specifically, using the third step of the Navigator, the founders designed a small portfolio of backup and growth options that they would keep open. This foresight laid the ground to early key decisions that have long-term consequences, like how they developed their drone or chose their brand name. In addition, it helped them clearly define which options they would place in storage for now (as focusing is about saying no more than anything else).

By employing the Market Opportunity Navigator, Flyability has not only figured out “Where to Play” it has mapped out an interesting growth path that is appealing to investors. To get a better sense of this process, you can view Flyability’s Navigator below, or read the full case study by clicking here.

Insights for VCs, Tech Transfer Officers, and Social Entrepreneurs

Identifying your arena of opportunities is not only key for startups and established firms, but for anyone dealing with technology commercialization. For VC’s, the macro-level perspective shows the market opportunities that can be addressed by a startup and lays out a clear monetization process over time. It also offers a portfolio perspective when screening initial or successive investments. If you are working for a Tech Transfer Office, a wide-lens perspective is essential for assessing the value of an invention, and for figuring out in which hands you should put it. Furthermore, if you are trying to address a social problem, the Navigator helps ensure you identify a market that allows you to generate an economic bottom-line in addition to your social impact.

Lessons Learned

- Lean Startup tools offer the details of “how to play,” while the Market Opportunity Navigator helps you to zoom-out to understand “where to play”

- There are multiple “starting positions” for your customer discovery journey

- Each starting point has different challenges to overcome

- What would be your most valuable domain?

- The Market Opportunity Navigator is an easy-to-apply framework for this process

- Worksheets and supporting material can be downloaded at www.wheretoplay.co

Filed under: Customer Development, Market Types | 2 Comments »